Making Middleboxes Someone Else's Problem: Network Processing as a Cloud Service

Making Middleboxes Someone Else’s Problem: Network Processing as a Cloud Service

The paper explores the idea that middleboxes (specialized network appliances, such as firewalls, intrusion-detection systems, web proxies, etc.) can become a cloud service, much like we have infrastructure as a service or software as a service.

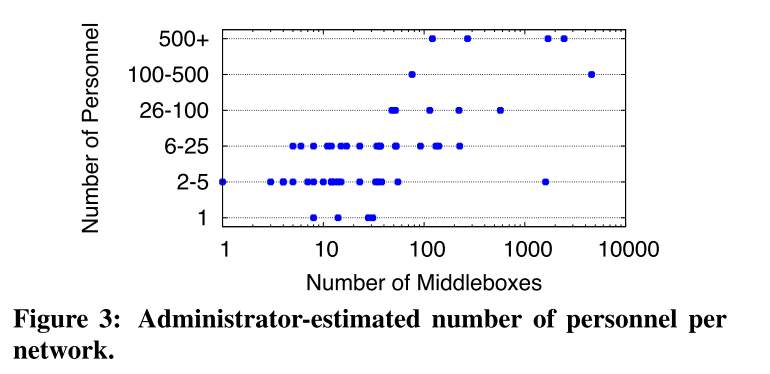

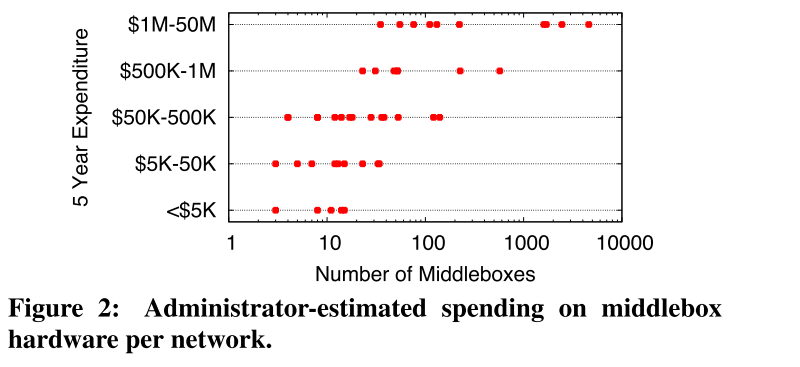

To better understand the use cases, context and pain points of middlebox deployement and operation in enterprises, the authors also performed an exploration of 57 enterprise networks: 19 small (<1k hosts), 18 medium (1k-10k hosts), 11 large (10k-100k hosts), 7 very large (>100k hosts). (thoughts: I assume hosts means workstations and servers using the network).

Moving Middleboxes to the Cloud

The middlebox deployement analysis revealed:

- Substantial middlebox presence: middleboxes are deployed (approximately) in as great numbers as L2/L3 networking devices.

- Varied human-to-middlebox ratio: vaguely, within 1 order of magnitude of each other. (thoughts: the paper mentions these are estimated so I wonder how well they are estimated)

- Deployment costs (thoughts: again, estimates, and it would have been interesting to have a per-middlebox cost, to get a feeling for economies at scale for large deployements)

General benefits of Cloud Middleboxes (same as cloud computing/storage):

- Pay-per-use: reduces the need for overprovisioning for peak usage or hardware failures.

- No upfront capital expenses: no need to buy the hardware, cloud middlebox provider benefits from economies of scale and one client’s idle is another client’s in-use.

- Reduced operational expenses: again, economies of scale, and reduced human-to-middlebox ratio, so lower cost per middlebox.

Specific benefits of Cloud Middleboxes:

- Trying without sunk cost: buy-the-hardware on-premise ecosystem means exploring new middleboxes and their features is costly.

- Decoupling features from hardware: on-premise middlebox hardware and software come as a package, so a change in (software) features forces purchasing of new hardware.

- Simpler configuration, monitoring: enterprise administrators can now configure and monitor policies (intentions) and no longer need to also to deal with middlebox-specific configurations and gotchas.

- Reduced failures, training: because of the specialized nature of middleboxes, middlebox misconfiguration is often (estimated) to be the common cause of failures, and this requires substantial amount of training to prevent.

(thoughts: evidently, the bigger the enterprise, economies of scale appear and the training and configuration managment efforts are amortized, as well as a purchasing power leverage with respect to middlebox OEMs. Still, profiting from these phenomena requies the enterprise to seize the opportunity and care enough to invest energy into negotiating with middlebox OEMs to, for example, provide a more programatic access to configuration so as to develop a unified middlebox managment and monitoring system.)

Appliance for Outsourcing Middleboxes (APLOMB)

Traffic and configuration will need to exchanged between the enterprise local network and to the cloud middlebox provider: the middlebox that was once sitting on the local network now sits in a cloud provider’s network. The middlebox needs to process traffic meant for the enterprise and the cloud provider needs to know how the enterprise wishes to configure said middlebox.

The authors propose an Appliance for Outsourcing Middleboxes (APLOMB). The APLOMB would be sitting at the edge of the enterprise’s network, communicating configuration and forawrding traffic.

(thoughts: while the authors address middleboxes that sit at the network edge, between the internet and the enterprise’s local network, and don’t really address intranet middleboxes)

Successfully outsourcing middleboxes to cloud middlebox providers means addressing three key points (thoughts: and a fourth, an assumed lowered cost):

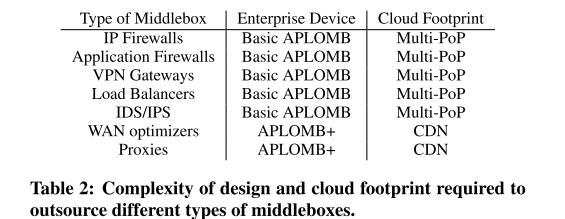

- functional equivalence: obivously, the cloud middlebox needs to provide the same service as an on-premise middlebox. What types of middleboxes can retain their functionality when outsourced?

- low on-premise complexity: the enterprise still needs to handle some complexity, even with outsourced middleboxes; this complexity needs to be low enough to warrant said outsourcing.

- low performance overhead: cloud middleboxes require traffic to wander outisde the enterprise network, and so latency and traffic volume overhead introduced by this needs to be minimal.

Design Considerations The authors list a few technical design considerations:

- Enterprise-side complexity after outsourcing: what must the enterprise keep track of and configure after middlebox outsourcing

- Redirection strategy: how will traffic be redirected

- Cloud provider footprint: what type of cloud provider would we want? One with closer points of presence (PoP) to ensure lower latency (e.g. a CDN) or maybe a bigger better-connected one but with reduced geographic prensence (e.g. Amazon’s AWS).

Redirection

The authors discuss three types of redirection:

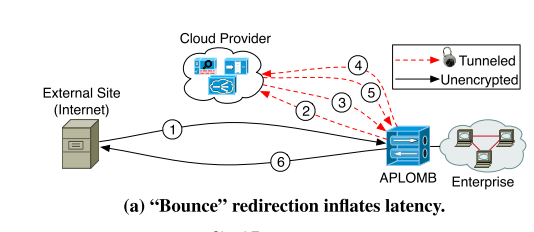

1. Bounce Redirection

All ingress traffic is first sent to the cloud provider for middlebox processing, returned to the enterprise. All egress traffic is similary sent to the cloud provider before returning to the APLOMB to be forwarded back to an external destination.

Pros:

- simple to configure

Cons:

- increasd latency, but manageable if round-trip time to provider is small

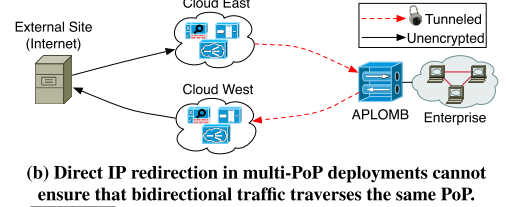

2. IP Redirection

Cloud provider advertises as the enterprise network IP, a sanctioned man-in-the-middle.

Pros:

- No roundtrip penalty like bounce (so less latency)

Cons:

- More complex to set up, change

- Multi-PoP issue: middleboxes usually need to maintain state (they need to see traffic going from client a to server b and vice versa to do their job correctly). Using IP redirection, these sessions are hard to keep track of/guarantee.

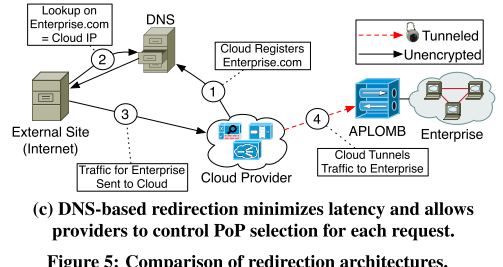

3. DNS Redirection

The cloud provider handles the DNS service. When a client asks for the enterprise network, they are given the cloud provider’s IP. Again a DNS-based authorized man-in-the-middle.

Pros:

- Simple to configure

- Control over paths

- Multi-PoP not an issue

Cons:

- Some legacy services don’t support DNS lookup

Performance: Smart Redirection

To improve latency, the authors discuss a DNS-based redirection they call smart redirection which uses several PoPs from the cloud provider, in hopes that a PoP might be geographically closer to a client connecting than another.

As such, the APLOMB needs to keep track of which connection comes from which cloud PoP in order to send the traffic back through the correct cloud PoP (and preserve the session for the middlebox).

In their tests, the authors have noted that 70% of cases have no (or negative) latency inflation when compared to a direct connection(negative latency inflation because the cloud provider’s PoPs are connected to client’s ISPs pretty well so they accelerate a leg of the journey). 90% of connections see a latency increase of less than 10ms.

Performance: Bandwidth Consupmtion

The authors envisage a APLOMB+, which is integrated general compression capabilities, to reduce bandwith consupmtion.

The authors explains that APLOMB+ compression would be protocol-agnostic, and therefore woulnd’t able to fully replicate performance provided by protocol-specific compressions in some specialized hardware.

Performance: Provider Footporint for Latency

The paper distinguished between Multi-PoP providers (e.g. AWS datacenters/regions) and CDN providers (presence in thousands of geogrpahical locations). In this case, CDN providers have a lower latency as they geographically closer.

From a latency perspective, the authors note that multi-pop providers are usually sufficient for client-server communication. However, some middleboxes require a low roundtrip between the enterprise network and the cloud provider; in these cases, a CDN-type provider is necessary: an Amazon-like provider provides a ronudtrip time of <5ms 30% of the time vs 90% of the time for a CDN-like provider.

They provide a table that summarizes their conclusions:

Implementation & Testing

The authors describe implementation details such as:

- what IP & service information the APLOMB would exchange with the cloud provider

- how failover would be handled

- how the cloud provider would handle scaling

- how policies would be configured by the enterprise administrator

- how the cloud provider and APLOMB exchange health and route information to optimize redirection

The authors then proceed to use as many off-the-shelf components as possible to build a proof of concept and show the barrier to entry is low.

They show that performance and bandwidth do not suffer using APLOMB (and sometimes there are gains).

Bandwidth Cost

The authors acknowledge that bandwidth is more costly when using Amazon’s services but propose that:

- a middlebox-dedicated company would be more sensitive to bandwidth costs

- even Amazon has a tier offering better pricing for high-volume users

- the bandwidth cost is offset by a foreseen decrease capital and operation expenses

Security

The paper acknowledges that cloud middlebox providers will face the same issues and questions as cloud compute and storage providers do, in terms of a third party processing and storing sensitive enterprise data.

They do note that data-in-transit in encrypted between the APLOMB and the cloud provider.