The Datacenter as a Computer (Second Edition)

Introduction

While a datacenter can contain a heterogeneous mix of applications, some applications are large enough to fit an entire datacenter; that is, the entire datacenter is centered around delivering one single application. For example, Gmail or AWS instances (from Amazon’s point-of-view, the application being offered is a hypervisor, they don’t really care what’s being run inside the hypervisor)

Effectively running one application inside a datacenter allows the designers of said Datacenter Application to think about the effects of orchestrating hundreds, thousands of servers.

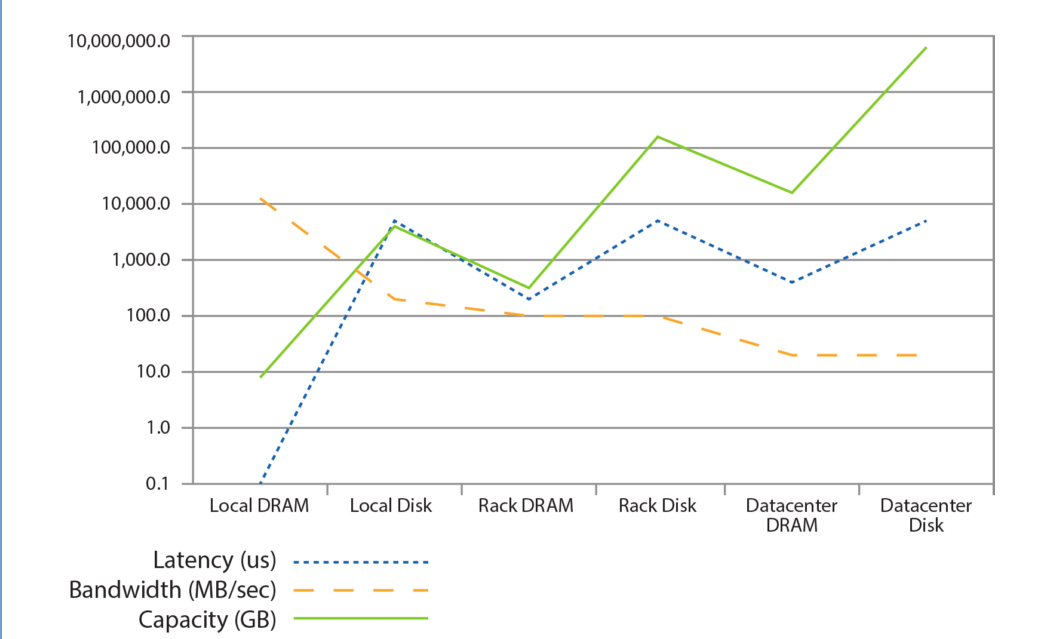

The hardware design of a server (CPU registers, cache levels, RAM, SSD) impacts how software is written; for example, we store frequently accessed data in RAM and we make sure persisting data is on non-volatile memory. If we have access to a GPU, we only send parallel problems to our GPU, and when we do send the data, we only send it in bulk because of the transfer cost from main memory to the GPU’s memory.

In the same way, we can design software to take into consideration the properties of servers available within a datacenter: instead of writing the software for the server, we write it for the datacenter. For example, if two servers are in the same rack, it’s faster (less latency) for the first server to access data, through the rack’s network, held by the second server in RAM than to access its own data stored on local disk. If we accept that servers, racks and the entire datacenter are all actually working together to deliver the same application, we can take advantage of such realizations.

Workloads and Software Infrastructure

Datacenter-Sized Internet Application

Parallelism: challenge is to not to find it but to efficiently harness the parallelism.

- Data-level parallelism from large swaths of independent data to process

- Request-level parallelism from a lot of simultaneous requests.

- Generally, they’re read requests but even write requests are sufficiently independent from each other and offer plenty of parallelism.

Workload Churn: behind stable APIs, code changes often, monthly if not weekly.

- Quick product innovation

- Hard to profile, optimise datacenter (things move too fast)

- New hardware is quickly taken advantage of, given the quick updates in software

Platform (Servers) Homogeneity: Not as much variation between servers, and server configuration, in a datacenter.

- Simplifies cluster-level configuration and logic (scheduling, load balancing)

- Reduces maintenance burden, supply chain and repairs

No Fault-Free Operation: Given the quantity, servers failing is a daily occurrence

- Server failures should be abstracted away by the cluster-level software

- However, when cluster-software can’t abstract it, the datacenter-sized application needs to consider some component is always failing

General-Purpose Computing System:

- Services running all have different needs, the hardware needs to do a bit of everything

- Hardware specialisation rarely makes sense: software changes too fast, specific hardware is a big static investment

Section 2.2 has a table of high-availability and scaling techniques (e.g. sharding, watchdogs, canaries, tail-tolerance)

Platform-Level Software

Basic server-level software (OS, firmware, drivers, libraries

Platform homogeneity and known environment means:

- Stripped down drivers, OS

- Optimisations for datacenter environment e.g. assume communication has low risk of packet loss

Cluster-Level Software

Software that makes the server a node part of a cluster; cluster sync, communication, accessing cluster services, offering services to the cluster

Resource Management:

- map tasks with desired properties (network, processing, storage, memory, ASIC) to hardware [Kubernetes would fit here]

- can take into consideration power budget, energy usage optimisations

Basic Cluster Services:

- Offer applications generic services like storage, message-passing, synchronisation (not every application needs to reimplement this)

Deployment and Maintenance:

- Sysadmin tasks (deploying images, versions, updating binaries, monitoring server health) becomes a burden in a datacenter

- Cluster-level software tries to help with those tasks and aid debugging these distributed systems

Programming Frameworks:

- Offer programmers frameworks for certain common-enough application-level software problems with orchestrating the hardware its using or helping to abstract away complexity e.g. orchestrate compute resources with MapReduce

Unstructured Storage:

- Blobs, consistency, replicated e.g. GFS, Colossus Structured Storage

- Varied products that trade off consistency, availability, schema flexibility, performance

Application-Level Software

Application-specific software, the thing using the other levels to perform work (Gmail, Maps, etc)

- Diverse and changing rapidly

2.5.1 - 2.5.3 Give a Nice Example for Application-Level Software

A Monitoring Infrastructure

Service-Level Dashboards:

- real-time signals needed from application deployments to take corrective action when needed

- can be few simple signals e.g. latency, throughput

- can be complex signals for large/complex apps/deployments e.g. trend to predict, compare, business-domain specific signals, provide a way to describe ever-changing relationship between signals

- avoid false positives (get ignored) or false negatives (late/no fix, noticeable to the user)

Performance Debugging Tools:

- Answers why performance is as is

- Not necessarily real-time, can be like profiling

- Blackbox systems: generally applied everywhere cheaply, less insight, needs to infer relationships from network calls

- Middleware systems: integrated with the application code/libraries, causal relationships established

Platform-Level Health Monitoring:

- still important to monitor explicitly, as application and cluster-level software tolerates hardware failures and might not produce strong signals

Buy vs Build

To use third-party solutions or build/modify in-house?

- Google tries to make us of in-house or open-source code that can be changed

- Build, instead of buy, means more work

- Build allows flexibility: quick turn around to fix bug, add features

- Build means addressing the problem at the right level

- Build means addressing specific requirements instead of market-wide problems (simpler, cheaper systems)

- Vendors might not be able to test/optimise if they don’t have Google’ datacenter scale

Tail-Tolerance

With enough scale, cannot guarantee all systems will perform well; for some requests, some arbitrary system will perform poorly.

That poorly-performing system will be the bottleneck of the entire request.

There are different strategies to deal with this e.g. have several servers redundantly handle the same part of the request simultaneously, in case one of them is the slow one (and hopefully the other performs well)

Hardware Building Blocks

How to choose cost-efficient hardware for the datacenter?

There’s different tradeoffs, (financial, technical) between buying wimpy (low-end servers) and brawny (high-end servers) components.

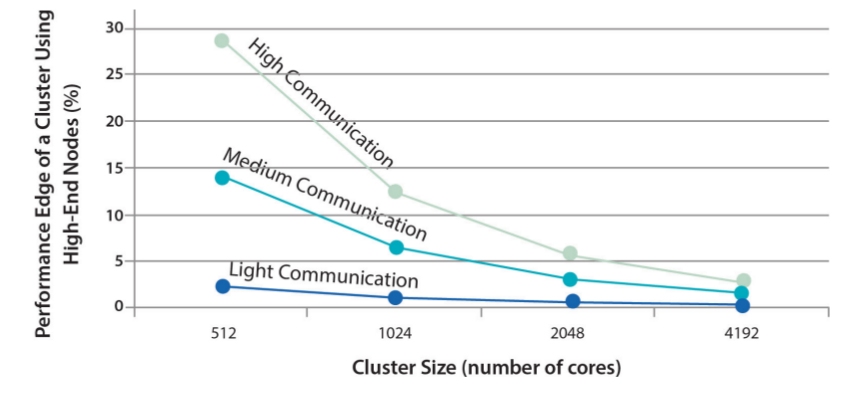

Using fewer Brawny vs many Wimpy

- If the workload can fit in a single Brawny server, inter-CPU communication is 100s ns versus 100s µs for LAN

- Using a simple model, “the performance advantage of a single 128-processor SMP over a cluster of thirty-two 4-processor SMPs could be more than a factor of 10×”

- However, if application needs many (2000+) CPUs, SMPs also need to be clustered also: SMP advantage almost vanishes

- Limit to many-clustered-Wimpies:

- communication/sync overhead can dominate CPU usage

- extra cost in optimising things for extreme parallelisation

- even parallelizable tasks can become less efficient to solve if divided into too-small tasks [reminds of “Scalability! But at what COST?”]

- bin-packing problem: if wimp CPU/RAM can only run 1.5 tasks, then 1 task will run and 0.5 will stay idle

- Interconnecting with higher-speed networks may be more expensive than buying SMPs

Hardware Design, Choices

- Software is more flexible, can be rewritten to adapt to new hardware realities e.g. going from wimpy to brawny, vice-versa

- Hardware should cater to the combined requirements of different application types that will co-use it, not become specialised per-application

- Fungible resources are used more efficiently, make resources network available, and the network capable to allow access

Networking

- Any-server-to-any-server communication means linearly scaling up network capacity is not a linear cost

- Single router device have limits to offered throughput

- Oversubscribing is common (4:1 - 10:1): we expect that not all servers will be using their full bandwidth at the same time

- Specialise the network segments (so the problem is no longer be a generalised any-server-to-any-server)

- Specialised storage network

- Networks are becoming less static

- VMs being moved break location assumptions SDN is sought out, allow more flexible networking

- Control plane centralised, moved away from routing device

- Networking optimisations/problems can be solved with a more global view of the network

- Fits the Warehouse Scale Computer (WSC) model which already uses centralised and cluster-level software to abstract away individual devices (manage them, update them, etc)

Datacenter Basics

- 70% of outages are human error.

Datacenters can generally belong to 4 tiers:

- (Most datacenters aren’t formally classified)

- Tier I: single path for power distribution, UPS, and cooling distribution, without redundant components.

- Tier II: adds redundant components to this design (N + 1), improving availability.

- Tier III: one active and one alternate distribution path for utilities. Each path has redundant components and are concurrently maintainable, that is, they provide redundancy even during maintenance.

- Tier IV: two simultaneously active power and cooling distribution paths, redundant components in each path, and are supposed to tolerate any single equipment failure without impacting the load.

Theoretical availability estimates used in the industry:

- 99.7% for tier II

- 99.98% for tier III

- 99.995% for tier IV

Power Systems

Power to datacenter floor

- (Outside) Utility Substation: high-voltage (>110 kV) to medium voltage (<50kV)

- Primary Distribution Center (Unit Substations): medium voltage to low-voltage <1000V.

- Low-voltage lines to UPS, UPS also connected to backup generator.

- (Inside the building) UPS wires to PDUs on datacenter floor

UPS

- Switches to backup generator when main is down

- Has temporary energy (e.g. batteries) as backup generator can take time (10-15s) to start

- Filters AC hiccups

- 100s kW - 2MW

- can be emergency power buffer

- traditional losses of 15% power, newer 1-4%

PDU

-

transform (some loss) and distribute power (75kW-225kW) to circuits (6kW each)

- per-circuit breakers (few servers are affected by a tripping)

- PDUs accept redundant power inputs, can switch between them

- more complex variations: parallel power to shared bus, fully power-redundant setups, and more

High-Voltage DC (reducing AC-DC transforms)

AC-DC/DC-AC conversions happen at the UPS and server’s power supply.

Conversion Reduction

One (oversimplified) way to reduce conversions is a single conversion from high-voltage AC to high-voltage DC and only use DC everywhere in the datacenter; after all, server components want DC.

This is complicated by the fact HVDC workers and equipment are still not mainstream.

Cooling

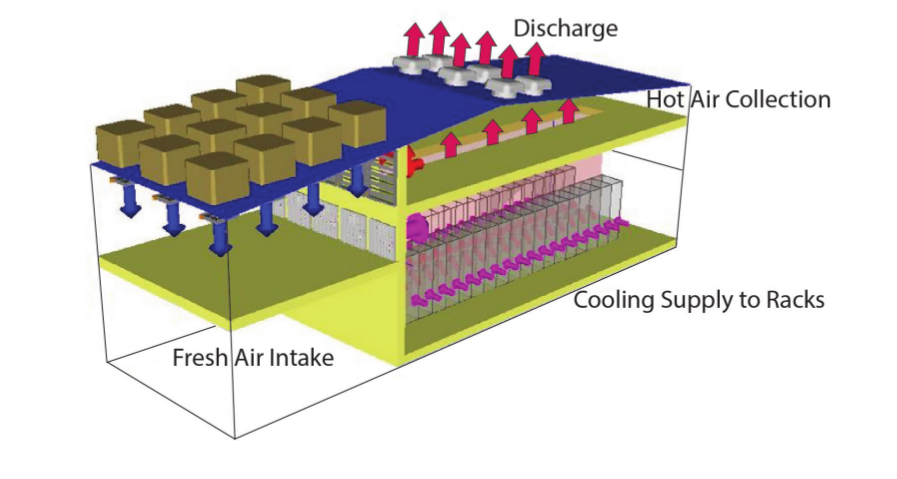

Fresh air cooling (open loop)

- Pump air from outside

- Circulate it under the raised floors

- Air will heat up, rise, and be pushed outside

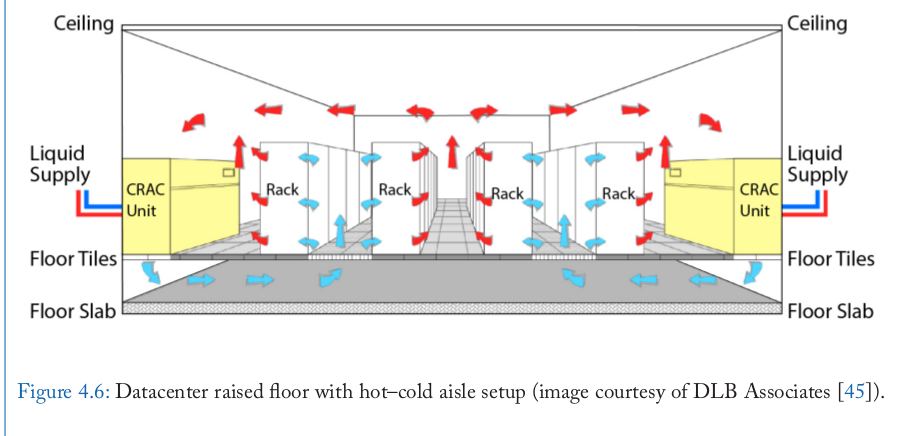

Simple Closed-Loop

- First loop: air exchange between the warm servers and a CRAC (computer room air conditioning) unit in the room

- Second loop: CRAC unit sends liquid to the rooftop to discharge the heat in the environment

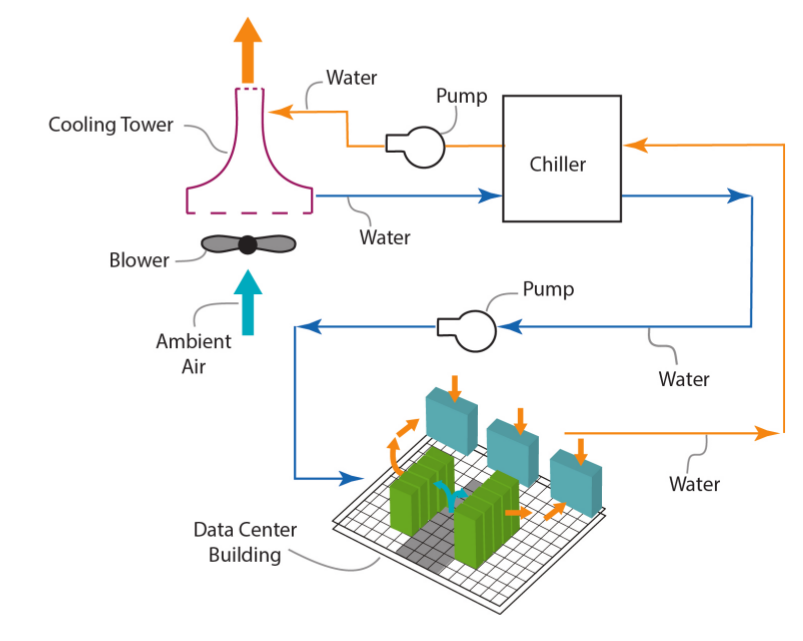

Three-Loop Cooling (one example configuration)

- CRAC is itself intermediary and sends warm water to a chiller (chiller is itself water-cooled)

- CRAC water and chiller water don’t mix, they transfer energy to/from each other through pipe walls

- Chiller cools CRAC’s water by running the CRAC water pipes in the chiller’s water basins

- Chiller’s now warm water is sent to the cooling tower

- Cooling tower uses evaporation to cool the chiller’s water

Tradeoffs

“Each topology presents tradeoffs in complexity, efficiency, and cost. For example, fresh air cooling can be very efficient but does not work in all climates, does not protect from airborne particulates, and can introduce complex control problems. Two loop systems are easy to implement, are relatively inexpensive to construct, and offer protection from external contamination, but typically have lower operational efficiency. A three-loop system is the most expensive to construct

and has moderately-complex controls, but offers contaminant protection and good efficiency when employing economizers.”

Mechanical and electrical components of cooling can add a lot (40%) to the power usage and thus cost (construction and operating) of the datacenter.

Airflow at Rack

The tiles of the raised floor, from under which the cool air originates, can have different perforation sizes; the perforations are changed depending on how much air flow we want to stream upwards towards the servers in the rack.

Upwards cold airflow must match the warm horizontal airflow the servers are generating.

If the cold airflow does not, some servers will ingest warm air instead of cool.

Crappy airflow requires cool air temperature to be lowered further, but this is more costly that simple proper airflow. Cost-wise, airflow is a limiter is power density (and in effect, how many servers per volume) .

In-Rack/In-Row Cooling

Cooling can happen at the rack or row of racks level directly: the hot server air is immediately cooled by cold water pipes running alongside the rack/row. In-Rack/In-Row can complement the CRAC or entirely replace it (effectively bringing the CRAC next to the servers).

Local Server Cooling

Liquid-cooled heat sinks over heat-dissipating parts, like CPUs.

Contained-Based Datacenters

Server racks put inside a 20ft-40ft container, each container have its own cooling, power, PDUs, cabling, lighting, etc.

Containers still need outside help from CRACs, UPSs, generators.

They provide higher densities due to better airflow control.

Energy and Power Efficiency

Power Usage Efficiency (PUE)

- PUE: tries to measure how efficient the datacenter facility is, power-wise

- PUE ratio: total power used in datacenter vs power used by the compute machine themselves (e.g. PUE of 3 (3:1) means datacenter operation consumes 2 units of power, compute consumes 1, thus datacenter consumes 2x power of compute)

- Recently-ish, PUE is at ~2

- Small datacenters don’t measure their PUE

- Historically, datacenter power efficiency wasn’t considered until 2010s

Problem with PUE

- non-uniform measurement of inefficiencies, despite guidelines

- marketing PUEs reported on theoretical best-world conditions

- error margins in PUE measurements due to insufficient data points, over time or device granularity

- PUE depends on the efficiency of compute servers too, so PUE changes as they change, even if the facility itself hasn’t changed

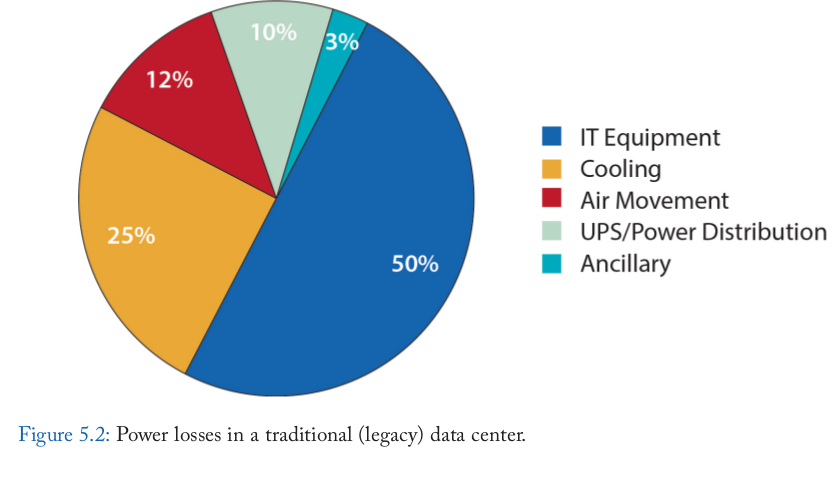

Efficiency Losses for PUE of 2

Server PUE (SPUE)

- Tries to measure how efficient the server non-compute components (e.g. fans, transformers) are, power-wise

- not standardised, but easy to define

- SPUE of 1.6 - 1.8 once common, 1.2 more state-of-the-art

Total PUE (TPUE)

- Combined PUE and SPUE (PUE * SPUE)

- TPUE of 1.25 seems like economically feasible limit

Computation Energy Efficiency

- TPUE excluded, what’s the power:computation ratio that servers provide?

- 5.2.1 lists some benchmarking tools and contexts

Energy-Proportional Computing

- Compute is not proportional to energy used.

- 100% utilisation might consume 1200W (12W/%)

- 50% utilisation might consume 750W (15W/%)

- 10% utilisation might consume 175W (17.5W/%)

- servers are rarely in the high-utilisation (And higher efficiency) ranges

- proportionality is not getting any attention from research and industry

- even better: optimise the efficiency for most-used load at the cost of inefficiency at high load (con: high load will be a bigger peak)

Low-Power Modes

- inactive low-power: components are off; huge penalty for reactivation (e.g. respin HDD platters)

- active low-power: general slow-down (lower CPU frequency, slower but not stopped platter rotation)

- active low-power can be maintained even with low loads (which are more common than idle states)

Software Role in Energy Efficiency

Software-wise, work can be distributed in energy-efficient ways.

- Encapsulation: lower-level (e.g. cluster-level) protocols/mechanisms must find ways to schedule work in energy-efficient ways without adding complexity on application-level software

- Performance Robustness: attempts at energy-efficiency mustn’t incur chances of service-level degradation

Power Provisioning

Determining Power Budget for Servers

- Server specs aren’t reliable enough

- Measuring live servers is better

- Still depends on application load

- Lack of energy-proportionality in computing makes estimation harder

- High application diversity means lower changes of all servers running on high load simultaneously

- Overbudget power and get idle, wasted, underutilized components (chillers, PDUs, USP)

- Underbudget and get outages

Oversubscribing Power

Study at Google datacenter showed:

- Over the datacenter server population, peak power usage reached 72% of maximum possible, could fit more (or budget less)

- Trend not uniform at every rack

- Oversubscription emergencies can be mitigated by reallocating power for low priority computing (e.g. batch processes)

- Underutilization can occur because of non-power relation reasons e.g. no space in rack, not enough cabling near underutilized PDU, breaker amperage limitation.

Trends In Server Energy Usage

CPU Dynamic Voltage and Frequency Scaling (DVFS)

- Older power-saving technique, reducing CPU frequency when load is reduced

- 2/3 load, 10% power savings (e.g. going down to 1.8 GHz)

- 1/3 load, 20% power savings (e.g. going down to 1 GHz)

- careful to not break latency SLAs

CPU Power Gating

- Shut off blocks of the IC that aren’t in use

- As we get more cores instead of higher frequencies, it’s a good technique

Energy Storage for Power Management

Proposed ideas: use UPS power to

- store cheap grid power, use when grid power is expensive

- mitigate power variability from wind-power

- compensate for peak power for oversubscribed power usage

- authors believe this is the most promising

- would require non-classic UPS, classic UPS don’t handle multiple cycles well

- not yet economically shown to work

Power usage is a big costly component in datacenters, complex problem at different levels

Modeling Costs

Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) composed of Capital Expenses (Capex) and Operational Expenses (Opex)

Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) composed of Capital Expenses (Capex) and Operational Expenses (Opex)

Capex: deprecated, upfront construction costs, server costs

Opex: recurring fees e.g. electricity, repairs, labor

TCO = datacenter depreciation (amortization) + datacenter Opex + server depreciation (amortization) + server Opex

Capital Costs

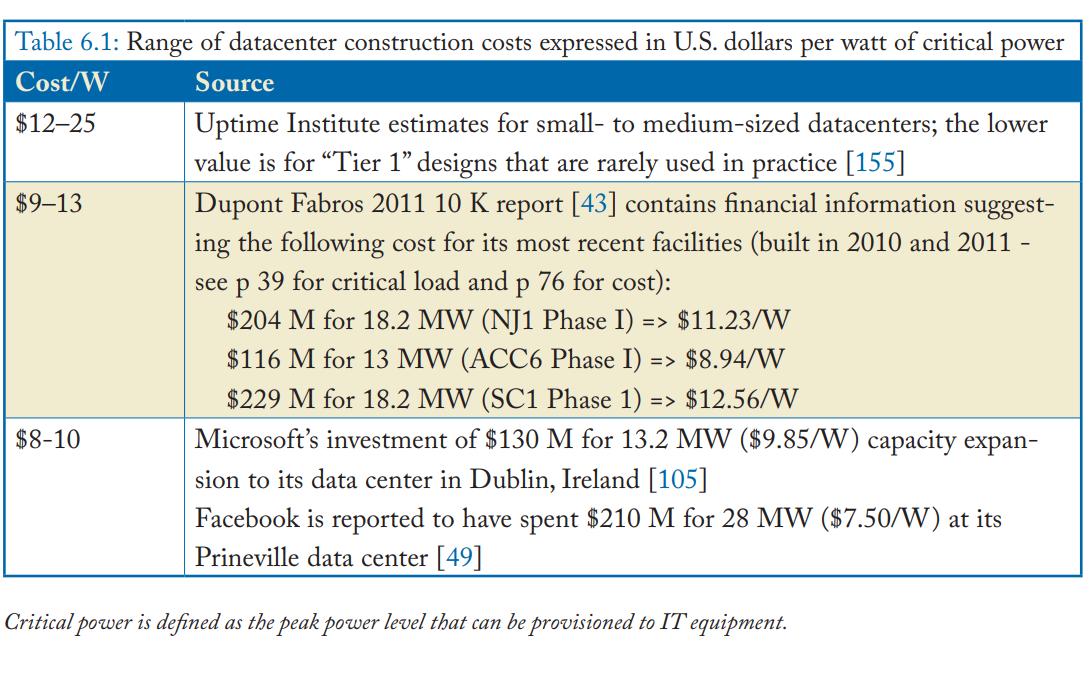

Datacenter

- Varies, depends on scope (and Tier)

- Very large and very small DC have disproportionate costs

- Rule of thumb: large DC cost 9-13$/W

- $/W is used because major costly components scale linearly with Wattage

- 80% Capex cooling, power

- 20% Capex building itself

- $/W should be reported per critical Watt

- critical Watt: Watt usable by the equipment at one time by design; redundancy, backup power doesn’t count

- critical Watt misreported

- $/square foot is a bad metric, doesn’t correlate well with cost drivers

- depreciation happens over 10-15 years using straight-line depreciation

- 12$ / W datacenter amortized over 12 years, cost is 0.08$/W per month

- at 8% interest rate, that goes up to 0.13$/W per month

- interest rates 7%-12%

Servers

- servers amortized over 3-4 years

- servers also use $/W

- 4000$ server consuming 500W is 8$/W

- Over 4 years, 0.17$/W per month

- At 8% interest rate, goes to 0.19%/W per month

Operation Costs

Datacenter

- Varies by geographical/environmental location (climate, taxed, local labor cost, etc)

- Varies by operation standards e.g. how many guards, how often is material inspected

- Varies by DC size, as some fixed expenses amortize better

- Multi-MW DCs in USA cost 0.02-0.08$/W, excluding electricity

Servers (Hardware Maintenance, Electricity)

- Varies by SLA

- Not including software stuff: licenses, sysadmin labor, DB admin, network engineers

Case Study in Section 6.3

Real-World Datacenter Costs

Worse than the model (many Watts planned, not many used)

- Not 100% of servers are in-use

- Extra datacenter construction, which remains empty for a while, happens to accommodate for growth without building-construction latencies

- Server power ratings assume fully loaded layout (e.g. max RAM, max HDD, max PCIe cards)

- can lead to overbudgeting power and building (too much) power and cooling accordingly

- Assumption of 100% CPU utilization for power budget, which is not generally the case but can be during spikes

Reserves

- Effective reserves of 20%-50% happen

- a datacenter rated for at 10MW of critical power will use an average of 4MW-6MW (plus PUE overhead)

Partially Filled Datacenter

“To model a partially filled datacenter, we simply scale the datacenter Capex and Opex costs (excluding power) by the inverse of the occupancy factor (Figure 6.3). For example, a datacenter that is only two thirds full has a 50% higher Opex. “

Cost of Public Cloud

“How can a public cloud provider (who must make a profit on these prices) compete with your in-house costs? In one word: scale. As discussed in this chapter, many of the operational expenses are relatively independent of the size of the datacenter: if you want a security guard or a facilities technician on-site 24x7, it’s the same cost whether your site is 1 MW or 5 MW. Furthermore, a cloud provider’s capital expenses for servers and buildings likely are lower than yours, since they buy (and build) in volume”

Dealing With Failures and Repairs

A system can be unavailable:

- due to failures

- but also maintenance, upgrades, repairs

A system with no failures can still be less than 100% available.

Hardware Fails

- Traditional software counted on ultra-reliable hardware

- At datacenter-scale, some hardware will always fail somewhere.

- The datacenter-scale application cannot expect no-fail hardware like legacy desktop applications can, for normal operation.

- Strive to provide cluster-level software that hides failure-handling complexity from application-level software.

Hardware no longer needs to run at all costs due to fault-tolerant software

Benefits:

- cost-effective hardware choices

- e.g. using non-enterprise grade servers despite their higher failure rate

- simplify operation procedures, no need for complex upgrade-transition procedures

- e.g. hardware upgrades are a matter of turning some of the old hardware off, replacing it by the new hardware, and starting up that up

- per-server recovery mechanisms can be simpler: a failed state can lead to a system going down and restarting instead of expensively (at least complexity-wise) trying to error correct in software and hardware

Storage with Hardware Failure

- Relying on RAID disks removes disk failure as an issue only

- There can still be other hardware issues that takes the whole machine down

- Use redundant storage on many more failure-prone machines instead

- More overhead on writes

- Better performance on reads

Expectations from Hardware When Using Fault-Tolerant Software

- Failure detection

- Reporting failures to the software

- Non-costly error correction should still be implemented e.g. RAM error correction

- Error correction should exist for errors which would be very burdensome to handle in software/cluster-level

Faults

- To design fault-recovery, need to know:

- fault sources

- statistical characteristics

- recovery behavior

- Fault severity:

- Masked Service Fault

- end-user is unaware of any failures/problems

- system performs as expected though maximum sustainable throughput is affected (over-provisioning can fix this)

- can be abstracted away in cluster-level software

- Degraded Service

- offers less-than-optimal experience but still useful

- needs design in application-level software

- e.g. gmail inbox might have some emails missing for a few minutes, new gmail messages delayed for send/receive, google search results missing some indexed pages

- Unreachable Service

- web-service might be unavailable (or unreachable) due to issues out of the datacenter control (e.g. transient routing errors, ISP issues)

- Google measures it’s availability as 99.9% (in 2014)

- Corrupted Data

- worst case: losing customer data

- not-worst case: losing operational data

- e.g. server configuration, operational logs

- not-worst case: losing product data that can be rebuilt

- e.g. losing some web pages that can recrawled

- Masked Service Fault

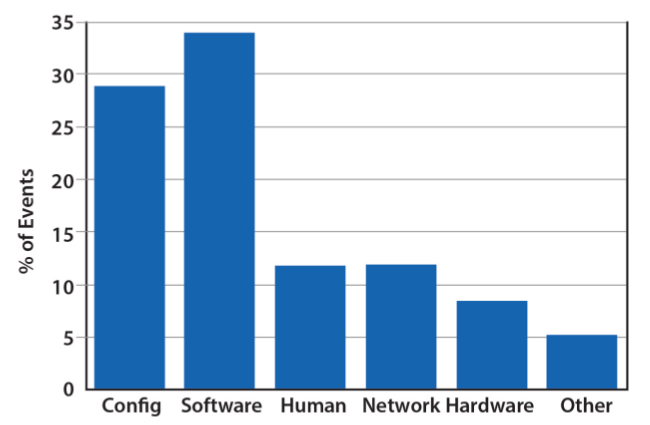

Service-Level Failure Causes

- few studies

- “fault-tolerant techniques do particularly well when faults are largely statistically independent”

- Hardware faults are generally statistically independent

- Software and operator faults have huge impact because they systematically affect multiple systems

- Google’s service-level faults:

Machine-Level Failures

- few studies

- generically, machines are unavailable on the scale of once a year

- one study: 55% restarts last <1 min, 25% <6min

- some batches of servers are unstable (new hardware, firmware, new bugs)

- some servers have early and frequent hardware failures that takes them out of the cluster (infant mortality)

- mature servers (i.e. survivors if infant mortality) “average machine availability is 99.84%”

- Hard to distinguish between transient hardware failure, firmware, OS bugs

- Software is still highest failure cause

Machine-Level Failure Causes

- DRAM Errors (Crash Report Google 2007)

- ECC corrects almost all errors

- 1.3% of machines see 1 uncorrected DRAM error per year

- most dram errors are non-transient: prevent the error by retiring a page of DRAM

- Disk Errors (different studies)

- errors non-uniform over disk population (i.e. bad apples)

- <3.5% drives ever see 1 sector errors over 32 months

- Disk error responsible for <10% crashes

- disk errors uncorrelated to temperature

Predicting Faults

- Prediction accuracy is not high enough to warrant preventive maintenance/repair/replacement

- Useless prediction: with 100% confidence, this disk will fail within the next 10 years

- Fault-tolerance systems mean hardware failure is not disastrous, just let them fail

Repairs

- Longer repair time, less cluster availability

- Repairs are expensive, pieces and labour

- Repair quality (was the problem identified and fixed) is important

- Due to fault-tolerance, repairs need not be immediate, can be scheduled for optimised technician time

Repair Diagnostics

- With many machines, Google sees patterns to aid machine-specific diagnosis

- Stores data for longer-term studies

- Can identify global patterns: bad batch of machines due to a common cause e.g. firmware

Tolerating, Observing but Not Hiding Faults

- Limits of the fault-tolerant system must be known

- i.e. given expected loads/desired availability, how many machines can fail, how many are statistically expected to fail

- Failures must be dealt with economically (in batches, not urgently) but without jeopardising the service

- e.g. 24-hour repair costs annually 5-15% of the machine’s value

- e.g. batched, slow, constant repairs costs 0.75% of a machine’s value

- Fault-tolerant system must be observed, when slack/overprovisioning is getting closer to critical